…one of the limitations is that it is very hard to distinguish working memory from other types of high-level cognitive control systems.

Dr Susan Gathercole

First, let’s not lose sight of the number of children we are looking to support. 15% of school age children are struggling with poor working memory capacity. Second, that working memory abilities are closely related to their academic performance in reading, maths and science and that “working memory scores predict the severity of their learning problems.” Gathercole and Alloway (2008: 48). Third, at the extreme end of the school distribution, children with general learning difficulties in English/literacy and mathematics were six times more likely to have both poor verbal and visuospatial short term memory and verbal working memory scores than children without SEN. Fourth, that working memory is more than a mere proxy for intelligence, with working memory at five years old a better predictor of achievement at 11 years old than IQ, (Alloway & Alloway, 2010). Finally, and very practically, one of the most common and crucial aspects of any classroom is following spoken instructions given by the teacher. This is particularly difficult for children with poor working memory capacities, where those instructions exceed the pupil’s verbal working memory.

So what is in the working memory box

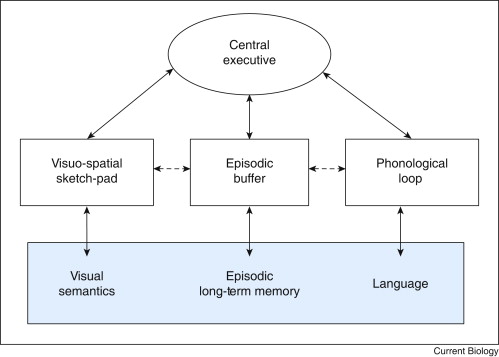

I should start by saying – working memory does not reside in a box. There are several theoretical models of working memory which differ in their views of the nature, structure, and function of the system. Most accounts of working memory distinguish between the storage-only capacities and the storage and processing functions of working memory.

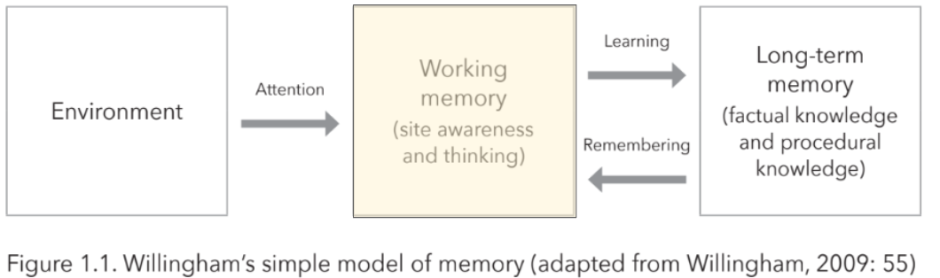

You have to start somewhere

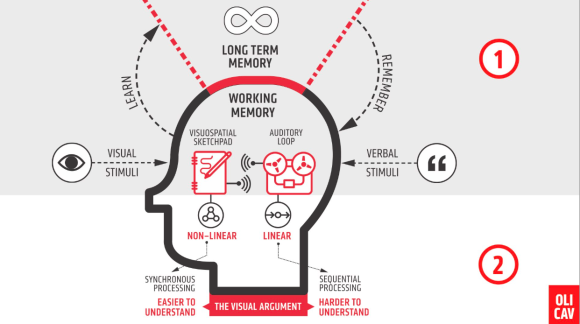

There are two domain-specific short-term memory stores, the ‘phonological loop‘ and the ‘visuospatial sketchpad,’ that are specialised for the temporary ‘maintenance and manipulation’ of verbal and visual and spatial information. These are ‘governed’ by a domain-general ‘central executive‘ linked to attentional control and responsible for ‘maintaining and manipulating information,’ coordinating performance on dual tasks, switching between retrieval strategies and inhibiting irrelevant information. The fourth component, the ‘episodic buffer,’ is an interface for the working memory components and binds information from subsystems and long-term memory, (Baddeley, 2000).

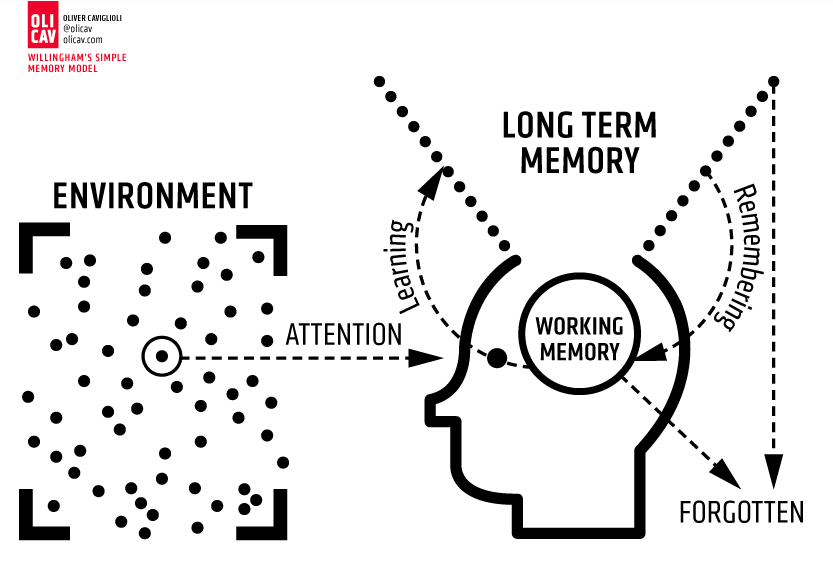

Why is attention so important?

Representations in working memory are transient; information can decay rapidly or can be subject to interference. So, working memory relies on active maintenance and manipulation of these representations (though thinking or conscious thought). This involves ensuring that the relevant representations or sense data are readily accessible and irrelevant representations or sense data are blocked or inhibited. As such, volitional attention plays a key role in working memory (Engle, 2002, 2018), “to either maintain information or to disengage from information.”.

However, working memory is not only limited by the storage mechanisms. This is the key point. It is also limited by executive attention, our ability to maintain focus on relevant information. As such, some researchers argue that working memory capacity is determined by how well we can maintain relevant representations of the information we are working with, in the face of competing or distracting information. In other words, executive attention is the predominant limiting factor of working memory rather than a precise number of items we can hold in mind.

Back to the working memory box – that is not a box.

Nuts and bolts of working memory quiz

| Name the two domain-specific short-term memory stores in working memory? | ‘ph______________ l_____’ and ‘v______sp______ sk____pad,’ |

| What governs the two short-term memory stores that is linked to attentional control? | ‘c_______ ex________’ |

| What is the function of the ‘episodic buffer? | The episodic buffer integrates working memory and long-term memory. |

The almost always inevitable model

Alan Baddeley (2022)

- The phonological loop – verbal and auditory information

- The visuospatial sketchpad – visual and spatial information

- The central executive – attentional control, / integrating information / making decisions / initiating action

- The episodic buffer – interface among working memory components / binds information from subsystems and long-term memory

Which prompts me to share Oliver Caviglioli’s model, based on Canadian researcher Allan Paivio’s dual coding theory, from his presentation, that layers the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad, upon his simple model of memory (without the central executive and episodic buffer).

Classrooms are largely complex adaptive systems. Teaching is complex and messy. As complex as they are, our pupils possibly need them to be less so. What is more, if knowing about cognitive load theory is as important as it is reputed to be, then teachers knowing about the theoretical architecture of working memory must surely be commensurate.

| Critical Teacher knowledge – working memory (part I) | Working memory – a simple model (part II) | What’s in the working memory box (part III) | Takeaways and reflections on – Working memory (part IV) |

Pingback: Critical teacher knowledge: working memory (part I) – Edventures

Pingback: Working memory – a simple model (part II) – Edventures