The final post in the Heitmann series. What have we learnt so far?

Adaptation enhances the benefits of practice quizzing and is therefore a suitable tool to further optimise the use of practice quizzing in educational contexts. Cognitive demand-based adaptations substantially increased the quizzing effect and be cautious when considering achievement motivations as an adaptive mechanism.

Field studies

In a field study that stretched across five weeks, conducted during a university course for 155 undergraduate pre-service teachers at Bielefeld University, Heitmann et al., (2021) took adaptive quizzing into the field.

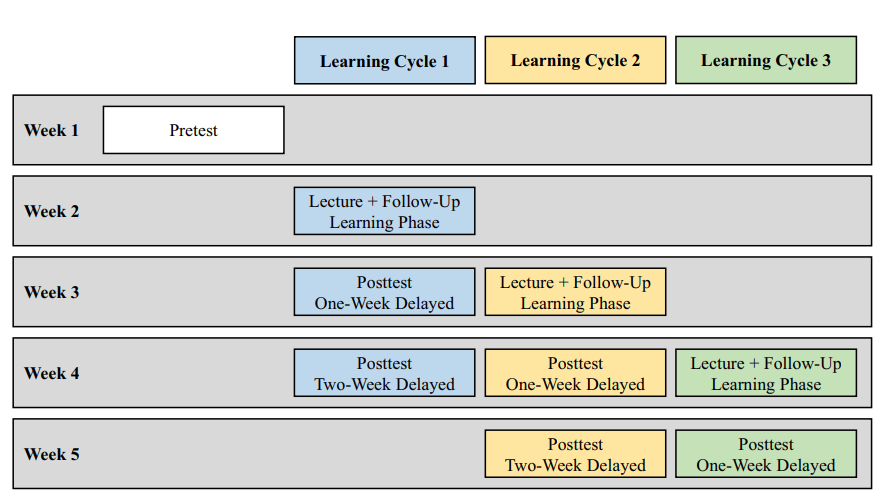

As the cognitive demand-based adaptive mechanism’s had trumped all other adaptive approaches in the laboratory setting, the field study compared a cognitive demand-based adaptive practice quizzing, a non-adaptive practice quizzing condition, and a note-taking condition across three learning cycles (each consisting of a lecture, a follow-up learning phase, a one-week-delayed posttest, and, apart from Learning Cycle 3, a two-week-delayed posttest).

What did we learn?

- Adaptive practice quizzing condition’s learning outcomes were superior to those of the non-adaptive condition on the two-week-delayed posttest.

- Adaptation reduced the quiz questions’ cognitive demand and intrinsic cognitive load.

- Adaptation of the quiz questions increases motivation, but not enough to make a statistically significant difference in comparison to non-adaptive practice quizzing (An increase in hope of success moderated the benefits of practice quizzing compared to note-taking in the laboratory study, no moderation effect was detected in the field study. A decrease in fear of failure did not have a moderating effect.)

- The results provide further evidence that the testing effect is not restricted to reproduction questions and extends to transfer questions suggesting that practice quizzing is a suitable tool to foster meaningful learning.

Cognitive demand-based adaptation offers an efficacy and practicability.

Heitmann et al., (2021) are also very honest. Experimental studies are “highly complex” and share four limitations, the first is worth exploring in depth.

In our study, the non-adaptive condition’s questions quickly rose in complexity, whereas, as the data show, the learners in the adaptive condition progressed rather slowly.

Heitmann et al., (2021)

Moreover that:

the adaptive practice quizzing group answered significantly more quiz questions than the nonadaptive group. Even though time-on-task was kept constant, this could of course also have had an effect on learning outcomes.

Heitmann et al., (2021)

I note this as interesting because as Dr Eglington continually reminds me that “…students have limited time to study, and thus the total time it costs is a vital consideration.” Should answering more questions be considered a limitation when “time-on-task was kept constant.” Are we not looking for a commitment or investment to learning from our students? Is that an important measure of applied motivation? In a field setting, what would happen if “time on task” on adaptive quizzing were discretionary? Would adaptive quizzing encourage a greater commitment to learning? I hope to be able to hear Dr Heitmann thoughts on the matter.

Second – sequencing led to naturally occurring interleaving, a desirable difficulty. Heitmann et al., (2021) suggest that future studies should systematically analyze the potential contribution of interleaving. (Which I can only see as a positive contribution). Third and fourth limitations were unavoidable – disruptions to learner routines as a result of control and validity measures and a lack of control of learning activities beyond the study.

Here is my only challenge

Heitmann’s dissertation taking retrieval practice, through to adaptive quizzing, then out into the field.

My only challenge comes from Heitmann’s dissertation.

Unfortunately, educators wanting to implement adaptive practice quizzing in their lessons face the considerable hurdle of finding a digital solution that supports the adaptive approaches evaluated in the studies described here.

Heitmann et al., (2018)

There are a handful of personalised retrieval platforms (quite a few frogs) and of course there is RememberMore. RememberMore adopts a very similar “performance-based” adaptation or personalisation mechanism using confidence-based assessment. One notable procedural difference is when that confidence-based assessment is made (let’s put that to one side for the moment). It is openly available for in-class quizzing, for personalised or adaptive quizzing and for unsupervised study. The app returning learning metrics and card insights.

Future Research – adaptive quizzing

Heitmann goes on to make a number of general points in her “Future Research” section of her dissertation that are worth responding to.

In theory, motivation would be expected to be higher in the adaptive than in the non-adaptive practice quizzing conditions because learners in the adaptive condition would be less likely to be underchallenged or overtaxed, both of which would likely lower motivation.

Heitmann – Dissertation

With the help of Leeds University Psychology Department, we found that pupils who used RememberMore reported higher higher self-confidence in class and in their own self-confidence in the subject.

“…the motivational advantages of adaptive questions being neutralised by the disadvantages of boredom and frustration from being confronted with the same questions over and over again.”

Heitmann – Dissertation

This is an interesting position. Quite possibly accurate.

Heitmann makes the point that higher-level quiz questions are actually more beneficial than lower-level ones. These cards then “trigger elaborative and generative processes, which increase storage strength.” In the case of Remembermore, these questions would be the cards learners have not yet retained or “mastered” and therefore have a greater probability of being presented. Of course, RememberMore also has “Notes” to explicitly elicit elaborative and generative processes. If accurate, one would foresee benefits to pupils outcomes.

Dr Heitmann closes with the tried and tested:

More research on adaptive practice quizzing is clearly needed to thoroughly assess this approach to optimising practice quizzing.

Heitmann – Dissertation

Questions

In a field setting, what do you think would happen if “time on task” on adaptive quizzing were discretionary?

There is a prevailing narrative for effortful retrieval. What is the time cost of incorrect answers?

The first two posts in the series: Adaptive quizzing higher learning outcomes and Adapting quizzing: perception of cognitive load #retrievalpractice.

Heitmann, S., Obergassel, N., Fries, S., Grund, A., Berthold, K., & Roelle, J. (2021). Adaptive practice quizzing in a university lecture: A pre-registered field experiment. 139 Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2021.07.008