After spending two weeks reflecting upon expectancy value theory and observing how individuals approach learning, I found myself applying a “motivational equation” to the context of my lessons, expectancy x value (- costs) = motivation, as swift pre-action calculation. I added the “- costs” to remind me that every task, in the eyes of pupils comes with both value and costs.

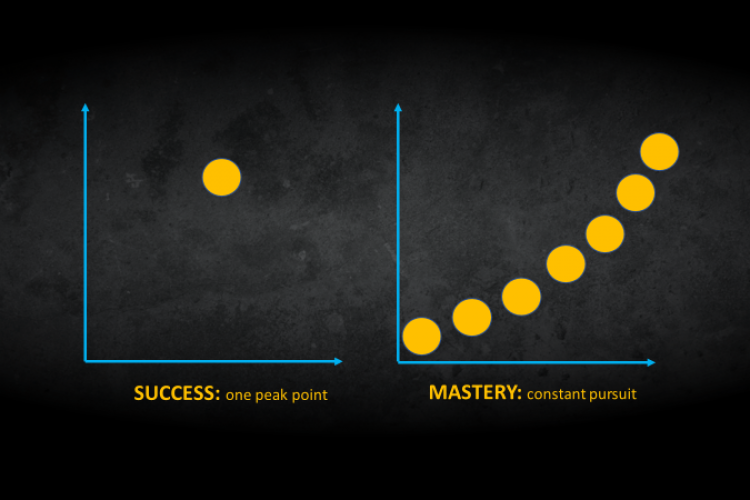

What I also now knew was that situational expectancies and values were more malleable to change than situational costs. That has taken some time to process and how I might apply that knowledge to facilatate learning. For sure we can do better than that cartoon character making their way up those oversimplified, perfectly staggered, achievement steps? Or any number of motivational statements to do more. You know – “the best way out of difficulty is through it,” type.

I am pleased to say, that the invested effort of understanding Dietrich et al., (2019) certainly made Tanaka and Murayama (2014) more accessible. Ready for the second recommend paper from Bridgid Finn @Bridgidfinn?

Tanaka, A. and Murayama, K. (2014) Within-person analyses of situational interest and boredom: Interactions between task-specific perceptions and achievement goals.

And it was a cracker! As far as research papers go that is.

Everyday… “interest and boredom” and the most frequently experienced emotions in the classroom (although not all researchers agree that interest is an emotion).

So interest – “a psychological state characterized by a feeling of positive activation or energy directed toward a particular task,” (Ainley, 2007) and it brings with it increased attention, deeper processing of information, better task organisation, and persistence.

Whereas boredom is “an affective state characterized by unpleasant feelings, a lack of stimulation, and low physiological arousal (Pekrun et al., 2010) and it brings with it a host of detrimental outcomes, withdrawal of effort and early withdrawal from school.

You may be interested to know, these emotions are first triggered by situations, and develop over time into relatively enduring predispositions. It is those dispositions we encounter as teachers. With most research adopting a between-person approach (those that are interested as opposed to those who are bored). What Tanaka and Murayama (2014) do differently, is they looked at within-person effects?

What to factors to explore?

First the factors facilitating interest and reducing boredom and second to test how individual differences in motivation, specifically, achievement goals moderate within-person relationships regarding interest and boredom.

Next – achievement goals, defined as “competence-relevant aims that individuals strive to accomplish in achievement settings,” Pekrun, Elliot, & Maier, (2009). Achievement goals have been researched to death and are thought to exert a broad influence on student outcomes. What is different here, is Tanaka and Murayama (2014) explore within-person associations of academic emotions in an effort to shed light on the under-examined, dynamic nature of motivational, cognitive, and emotional interactions.

What factor did Tanaka and Murayama (2014) focus on to evaluate interest and boredom? Subjective task perception.

Subjective task perception – “a student’s personal evaluative cognitions with regard to, for example, an academic course.” In teacher speak – the subject, the lesson. Which are in turn shaped by task-specific evaluations. These are driven by perceptions of expectancy, utility, and difficulty. Sounding familiar?

- Perception of expectancy – one’s belief about how well one expects to perform a given activity and the prospective perception of the impact of current effort on future outcomes.

- Perceived utility is one component of task value along with attainment value, intrinsic value, and cost. It refers to the instrumental usefulness of a task to attain present and future goals. Tasks with utility value are relevant to other tasks or aspects of a person’s life beyond the immediate situation. “Why do we need to learn this anyway?”

- Perception of difficulty is the judgment of the difficulty level of the task.

These three factors play out to either increase or decrease, interest or boredom.

For example, high expectations of success may be positively related to interest and negatively related to boredom. High utility content may facilitate interest and prevent boredom. Conversely, when students cannot detect meaning in the activities, boredom may result. Or where a class is perceived to be difficult, that perception may decrease interest and increase boredom.

Again, to remind myself, as much as anything, most studies to date have explored the relationships between task-specific perceptions and emotional experiences at the between-person level. Tanaka and Murayama (2014) were interested in within-person associations. Could we expect greater interest and less boredom in learning situations that students perceive as high in expectancy and utility and low in task difficulty? And whether achievement goals influence these within-person relationships? If you remember, the driver for this reading in the first place was to find out how “desirable difficulties” play out in self-directed and self-paced, spaced retrieval practice.

What did Tanaka and Murayama (2014) predict?

- mastery-approach goals would weaken the negative relationship between perceived task difficulty and interest,

- performance-approach goals would strengthen the positive relationship between perception of expectancy and interest, and that,

- performance-avoidance goals would strengthen the negative relationship between perception of expectancy and boredom.

In part 4 I will share their procedure, results and conclusions.