Do we have a terminology problem – yes. I think so. Comically highlighted by @C_Hendrick.

‘Retrieval practice’ the ‘testing effect’ or indeed test-enhanced learning is the case in point. In fact, Dr Agarwal asks us to ‘stop calling it that,’ and I considered her advice very carefully indeed before titling the book Test-enhanced learning. Dr Perry in his forward acknowledges the “troubled history” and “regrettable mistrust and even aversion to the term.” The T-word has also acquired a damaged reputation at every layer of learning, for pupils, teachers and school leaders.

Onto my third challenge, having shared my Carl’s scoffing of retrieval and testing and previously sharing my frustrations with the use of the term storage.

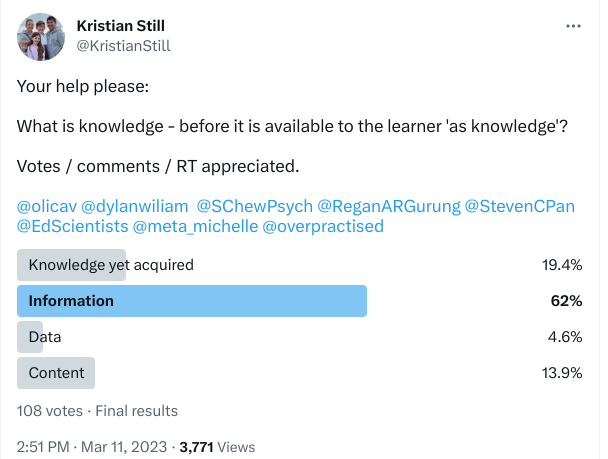

What is knowledge, before it becomes knowledge?

What is knowledge? What comes before knowledge?

Within the field of cognitive psychology, before something becomes knowledge, is often referred to as “raw information” or “raw data.” Brendan Schuetze @BA_Schuetze contributed, “material to be learned.” Lastly, Jon Owen @JonOwenDI offered “sense data.” This refers to the stream of sensory input that the brain receives from the environment; sounds, sights, and sensations, “meaningless and unordered before it is screened.”

Jon added:

The process of all behaviour is reception -> screening -> planning -> directive -> response.

Jon Owen

It turns out, there is another, epistemological view of knowledge – “cognitive success.” An attempt to understand what it is ‘to know,’ and how knowledge (unlike mere true opinion) is good for the knower.

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge, how it is acquired, justified, and evaluated. Within epistemology, “cognitive success” is often discussed in terms of the justification of beliefs, with the focus being on how individuals can determine whether their beliefs are true or not. Cognitive success is closely related to the concept of knowledge itself and defined as a justified true belief. This means that for a belief to count as knowledge, it must be both justified (supported by evidence or reasoning) and true (correspond to reality). Perhaps that brings me a little closer to what comes before “cognitive success,” – justified true beliefs?

The importance of sleep

After posting, Jon came back to me, reminding us that “unlike in philosophy, in cognition there is no onus on knowledge to be ‘true.'” I see his point, and I also respect that fact that whatever we name it, information/knowledge/cognitive success, “right or wrong [it] is used in exactly the same way.”

Teach a child that all fractions are less than one and he will behave exactly as if all fractions are indeed less than one… a learner can’t distinguish between the two. S/he is learning the information content. He will treat teaching that is untruthful and misleading just the same.

Jon Owen

Importantly, Jon and I rested on a mutual point. The importance of prior knowledge. That it is prior knowledge is, in the form of a gestalt or organised patterns or structures composed of sense data points (a more common reference for teachers is schema – though subtly different.*), transformed by incoming data and are transformed by it simultaneously.

Stepping back from epistemology, back to cognition

Cognition, focuses on how we (the brain) processes “sense data” to create knowledge. As Matthew Evans @head_teach contributed, “the creation of something new stimulated by something (or some things) else.” Undoubtedly, a complex process that involves perception, attention, memory, and to which I now include beliefs, and other cognitive processes, that allows learners to extract meaning and making connections to prior knowledge.

An ever on-going process, ‘sense data’ is perceived / received and screened. It is encoded (retrieval-encoding), connected with prior knowledge, possibly consolidated, organised, synthesised, and if so, stored as knowledge. This knowledge must then be maintained and is used to guide behaviour and decision-making.

More only doubt, is that so little sense-data is processed that is not almost instantaneously connected with prior-knowledge through the simultaneously process of retrieval-encoding.

How does this link with test-enhanced learning

Learning new terms is not an all-or-nothing affair—the more we know about a term, the more we know about the relationships between it and other terms.

Ben Wilbrink

On Tuesday with VNET Education CIC and on Friday with TTCT, teachers spoke of drowning under the weight of the curriculum. I was asked how I might take on that challenge? My answer is two fold.

- Define, code and sequence the essential knowledge.

- Leverage the direct and indirect benefit of test-enhanced learning in class and for unsupervised learning

Class time is too precious for introducing all the “sense data” or information required for cognitive success in our current exams system.

Testing, quizzing, and various other retrieval modes that leverage the benefits of test-enhanced learning are effective in both low and high fidelity settings, in both class and unsupervised settings.

We all know that the pupil who gives a correct definition response for a requested term shows that s/he ‘understands’ the term and uses it correctly. However, giving a correct definition is not a sufficient condition for the conclusion that the pupil knows the meaning and application of the term.

Recommendation

Teachers use unsupervised learning to introduce the required sense data / information – flashcards or knowledge organisers (that are not really organisers of knowledge but powerful lists). Reinforce unsupervised learning with in-class expedited quizzing and self-assessment. Use directed time to teach the meaning and application of knowledge.

My thanks to Jon Owen for his conversation, as ever.

Twitter poll results.

Pingback: Domain-specific prior knowledge and learning – Edventures