For the past three years, in developing my English teaching pedagogy, I developed a professional interest in production effects, initially with reference to retrieval practice design and vocabulary acquisition and latterly with to proofreading and editing.

Production effects: the difference in memory favouring words read aloud relative to words read silently during study.

Icht et al. (2014)

Production effects also align with a range metacognitive strategies that include a production component such as ‘read aloud – thinking aloud,’ sometimes referred to as ‘think-alouds,’ walking-talking mocks and live modelling.

Why teachers should be interested in production effects

Produced items have the “additional information that they were spoken aloud encoded in their representations, and this information is useful during retrieval” Macleod (2011: 1198). It plays to the intuitive notion that “when an event or an element of an event stands out from its surrounding context, we remember it better,” (2011: 1198). This ‘distinctiveness’ is considered an ‘active ingredient’ in the production effect, Ozubko and MacLeod (2010). It is most certainly nothing new – visit any primary setting and you will hear “I say, you say” routines. Alternatively, seek out the work of Dr Anita Archer.

Rather interestingly, production effects robustly extend to situations in which another person does the production however the benefits are “largest when the production is done by oneself,” Macleod (2011: 1201).

Production effects as an active ingredient when proofreading and editing

With a growing and deepening commitment to metacognitive practices, I have adopted four distinct phases of teaching writing.

- Planning (task management, planned thinking time, pre-selected vocabulary, learning loops – what worked last time?)

- Planning on the left of a double page spread. Drafting starts on the right.

- Drafting – “Plan the work: Work the plan.” Task and time management. Use of structure strips.

- Editing – planned proofreading and editing time (task management 80:20). Read-out-loud proofreading (and routines for class, context dependent)

- Feedback and action

- warm assessment / practice: whole class feedback, live marking, use of success criteria, self-assessment, peer review and dotmocracy

- cold assessment: whole class feedback, dot and circle marking, questions as feedback, learning loops (what worked?), redrafting work – final piece.

Here is the connection. Editing is a distinct phase of writing promoting the idea of iterative work (I have not referred to it as proofreading). I encourage pupils to read their own work out loud – even though we look/sound/feel like a prune. Up until my introduction to production effects, it was largely based on a teacher’s hunch, made up of various snippet of knowledge.

First, have you ever seen the ‘nonsense script’ you can read despite it being littered with errors? I had a hunch that pupils / I made similarly self-preserving corrections when editing our own work.

it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae.

it doesn’t matter in what order the letters in a word are, the only important thing is that the first and last letter be at the right place.

Second, have you ever been asked to look at a finished piece of artwork in the mirror. What looked finished or polished – can often look very unfinished when flipped. In fact many artists intentionally flip their canvas to expose errors.

This is how I first learnt of the ‘mere-exposure effect,’ or the ‘familiarity principle.’ A psychological phenomenon by which we tend to develop a preference for something merely because we are familiar with it. The effect has been demonstrated with paintings, architecture, branding, faces, word frequency and even sounds. What about our own written work? Work we read over and over again. Have I got you nodding in agreement yet?

Third, that speaking and ‘hearing’ the text helps discriminate various aspects of the text, making parts of the text distinctive, that ‘silent reading’ may fail to expose – both good and bad. Pacing,

the production effect and third the additional benefits to ‘hearing’ the text or written work.

- Pacing, variation of sentence length and rhythm. Add to that, awkward transition. Think learner drivers and gear changes.

- ‘Wordiness,’ or what I call ‘word padding.’ I have learnt that novice writers value padding. Reading out loud helps to identify words for deletion – this was exposed in the mini sagas last term.

- Clarity – speaks for itself.

And lastly, reading out loud would leverage the aforementioned production effects.

Hence I encouraged pupils to read their work out loud as an antidote for the ‘familiarity principle.’ To auditorily reveal technical errors hidden in plain sight, very possibly read and passed over and over. Reading out loud was my equivalent of flipping the canvas.

Cushing and Bodner (2022)

Last week The Learning Scientists reported on the Cushing and Bodner (2022) paper that examined two easy-to-implement methods to use during proofreading.

- Reading the text aloud

- Using disfluent text fonts (harder to read text fonts – Sans Forgetica)

What did we learn?

The focus here is ‘reading the text aloud,’ as it is openly available to pupils in both class and examination settings. Relative to proofreading silently, proofreading aloud improved error detection. Proofreading in Sans Forgetica either impaired or did not help error detection.

Several reasons were put forward for these benefits: increasing time on task and attention, providing auditory and articulatory processing (as explored above), and enhancing text comprehension. Perhaps the most interesting finding was that despite the quite clear and obvious gains of proofreading aloud, students rated reading silently and aloud the same both before and after the task. It is not the first time, nor the last time, we will encounter illusions of competence in learners.

Re-reading silently is comforting.

Takeaways

Regularly adopt ‘I say: You say,” strategies – leverage production effects. See Dr. Colin MacLeod “I said, you said,” paper or visit any primary classroom.

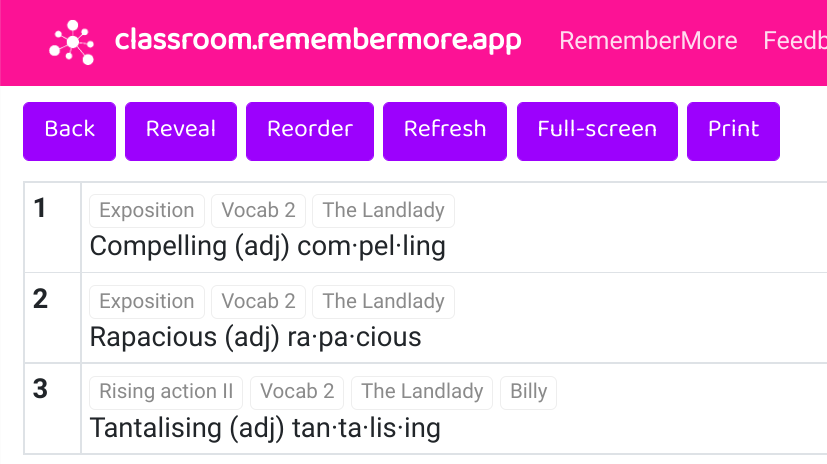

When presenting new vocabulary – model and support how the word is spoken. Make connections where appropriate, here the Year 7 Short Stories vocabulary is connected with the characters.

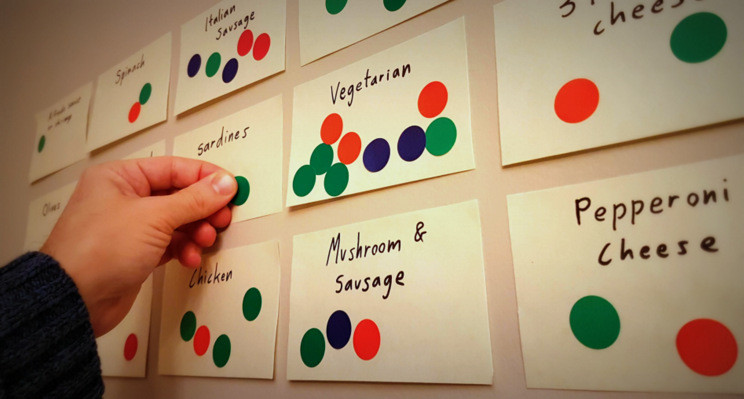

As for the logistics issues. If pupils are reading their work out loud, it will make for a noisy classroom. Fortunately, we have fantastic pupils and operate a four-out-at-any-one-time rule during the editing process. Pupils add their name to a roll list on board, striking it off when they return to make green pen edits.

MaisyArrabella- Gracie

- Alfred

- Tony

- Caghan

If nothing else, now we have evidence that reading out loud improves proofreading.

Further investigation shows that ‘out-load’ applies to speech synthesis. Using the speech synthesis enabled students to detect a significantly higher percentage of total errors than silent proofreading (as does having the text read aloud by another person). Read Aloud is available for Microsoft Office and Microsoft 365 and ChromeVox can be initialised with the short cut CTRL+ALT+Z.

Pingback: Plans, meso-cycles and spirals (part 3) – Edventures