In case you missed the first post Getting it wrong helps to get it right, the point was, the act of retrieving information from long term memory benefits learning. Retrieval, even unsuccessful retrieval modifies that memory, promotes consolidation (storage), and slows forgetting OR surprisingly, or primes or potentiates future learning for that memorry,

As ever, we are crossing multiple lines of research enquiry, retrieval, feedback, motivation, metacognition. The finding that when given corrective feedback, errors that are committed with high confidence, are easier to correct than low confidence errors, Metcalfe et al, (March 2011), and even low confidence errors benefit of errorful generation.

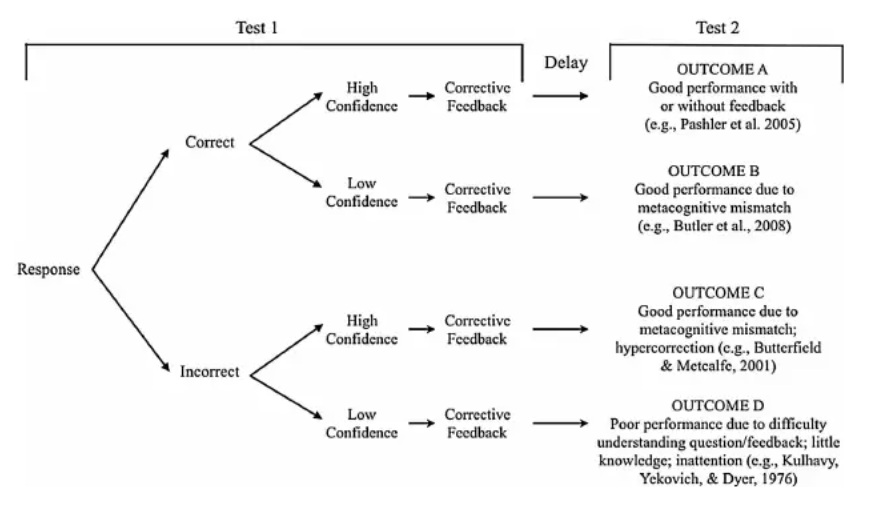

A weekend’s research and reading also led to Griffiths and Higham (2017), exploring four potential outcomes to a posed question where the learner receives corrective feedback immediately following each response.

Outcome A you will be familiar with. Feedback is somewhat “superfluous.”

Outcome B the lucky guess. Here a “metacognitive mismatch” is corrected.

Outcome C introduces the heavily evidence hypercorrection effect. Where high confidence errors benefitting from the “surprise” corrective feedback. The surprise leading to learners paying more attention to the correction, leading to greater re-encoding and storage of the correct answer for next time.

Outcome D Is the focus of this post.

Kulhavy et al. (1976) argued, “people make low-confidence responses primarily because they have difficulty understanding the material, the question, or both…If a student is having trouble understanding what he reads, providing feedback after he guesses at an answer should do little to improve comprehension.”

It highlights two key points. The quality of the re-instruction. The importance of corrective feedback.

Griffiths and Higham (2017) study is worth reading, if for the cunning and tricky of the questions they employed.

How many of each type of animal did Moses take onto the Ark?*

- 0

- 1

- 2

- 4

The question is likely to induce the error “2” instead of the correct answer “0.” The question refers to Moses instead of Noah.

If you have encountered this trickery before, you are likely to have benefitted from the hypercorrection effect and unlikely to have been fooled twice. Otherwise, I suggest you fell foul of the Moses Illusion.

If beer is produced in a brewery, what is produced in a ginnery?

- Cotton

- Gin

- Wool

- Vodka

Now I doubt you will allow me to trick you twice and you are probably skeptical. Even thought you know intuitive answer would be “Gin” you are hesitant and rightly so. The correct answer is “Cotton.”

Critically, what drives these error correction mechanisms?

Griffiths and Higham (2017) concluded high-confidence errors were better corrected when compared to low-confidence errors – the typical hypercorrection effect. However, low-confidence errors to trick questions were just as likely to be corrected as high-confidence errors. For trick questions, most surprisingly, it was not confidence or surprise that predicted of error correction. Rather, they concluded that for some types of material, there is an effortful process of elaboration and problem solving prior to making low-confidence errors that facilitates memory of corrective.

Bjork, R. A. (1975). Retrieval as a memory modifier: An interpretation of negative recency and related phenomena. In R. L. Solso (Ed.), Information processing and cognition: The Loyola Symposium (pp. 123-144). New York, NY: Halsted Press.

Griffiths, L., & Higham, P. A. (2018). Beyond hypercorrection: remembering corrective feedback for low-confidence errors. Memory (Hove, England), 26(2), 201–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2017.1344249

Metcalfe, Janet; Finn, Bridgid (March 2011). “People’s Hypercorrection of High Confidence Errors: Did They Know it All Along?”. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 37 (2): 437–448.

Kulhavy, R. W. (1977). Feedback in written instruction. Review of Educational Research, 47 , 211–232. doi:10.3102/00346543047002211

Pingback: Making Chemistry easier – Edventures