Exams season is upon us. With hindsight, I should have written and posted this sooner.

This post focuses on revision for long-term retention. That is when the period between learning and testing is greater than at least one day. That may not sound long term however you will acknowledge that most pupils still invest heavily in cramming the night, or even morning before an exam. And second, most test-enhanced learning research papers are classified as “Near” (74%) research – where the post-tests are completed in 1 day or less, 91% in 7 days (Donoghue & Hattie, 2021). Finding long-term post-testing or “Far” research therefore, reflective or revision schedules, is hard to find.

Long-term revision

Is there a benefit to generating your own revision materials, specifically generating questions? Yes.

Medium to large effects on comprehension, recall, and problem solving are reported, for a more extensive overview, see Song, (2016). Generating questions specifically, are thought to stimulate “deeper processing and reflection” of the learning material as well as benefiting from the gains associated with re-phrasing and paraphrasing, as well as retrieval practice, when compared with re-studying.

Note however, that pupils will need training on how to generate questions effectively. In addition, the learning material covered in many of these papers was relatively short and only short-term effects were examined.

A researcher you may be familiar with, Barak Rosenshine, explored the effects of the generation of questions on comprehension across 26 studies. Again with training, pupils benefitted from medium to large gains (g= 0.61) and short and long-term effects on the comprehension of the studied material, (Rosenshine, Meister, & Chapman,1996).

Without training, learning gains are less frequently reported and less pronounced. The question then, what is the time cost of question generation training? When that time could be applied to other strategies. Is there a motivational cost tied to revision tedium?

Testing

So we have two points here to explore:

- Generate questions as testing

- Testing on questions generated by others

Questions generated by the learners themselves could be seen as a form of testing itself because the previously processed information must be retrieved in the generation phase to formulate the question and answer. Of course, this will be followed by testing on the questions generated. Testing on questions generated by others then, a discrete testing strategy. An important question is whether both strategies yield similar effects?

Studies that compared the effects of testing and question generation are often based on short texts, “Near” delays and most critically, conditions were often not comparable in terms of time investment and the material covered. In general, I found proportionally more “larger” benefits (effect-sizes) of testing than when compared to the benefits of generating questions. Both strategies contribute to revision, however I would describe the findings as inconsistent, as did other researchers, see Bae, Therriault, and Redifer, (2019) and Ebersbach et al, (2019).

Food for thought?

Generating questions could arguably be more favourable than testing, given the cognitive processing in the generation of questions and answers, whereas, testing could arguably be more efficient (no training requirement, greater retrieval attempts and access to the correct response).

Re-studying

Re-study or re-reading is often reported as the preferred revision approach by students. Most of the benefit of rereading appears to accrue from the second reading, with diminishing returns from additional readings. You will find frequent references stating that re-reading is “ineffective,” or as “passive.” You will read comments highlighting the dangers of “fluency” and “familiarity,” during a subsequent re-reading. That is not to say that distributed rereading is not helpful, just that a students time could be better spent using another strategy.

Generate questions, testing or restudy for long term revision

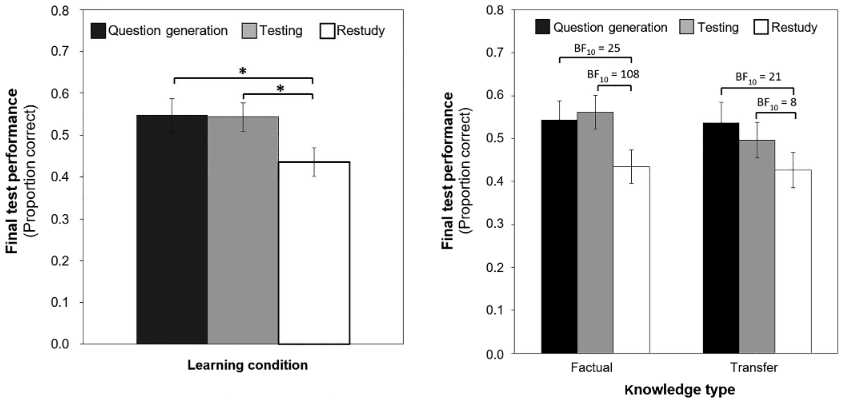

Ebersbach et al, (2019) tackled this important question, specifically focusing on “Far” or long-term benefits of revision.

82 psychology students. New course, new topic (ruling out confounding prior knowledge). About 20 min before the end of this lecture, students were informed of an extra learning phase from one of three conditions.

3 groups or conditions.

- In the generating questions condition, students were instructed to formulate one exam question in an open response format for the content of each slide and to also provide an answer to the question based on the relevant keywords that were printed in bold. (Hence the students were not required to identify the relevant aspects – it had already been done for them.)

- In the testing condition, one question per slide was formulated referring to the bold keywords. The students’ task was to try to answer the questions first without help and to only look up the answer in the slides if they were not able to provide an answer.

- In the re-study condition, the instruction was to go through all 10 slides and memorize the content.

A surprise test one week later on 10 factual questions and 10 questions that required the application of knowledge beyond the bolded words.

There was even an assessment error in the final post-test that had to be removed from the analysis – how about that for authenticity!

Furthermore, they made every effort to ensure that the conditions were “maximally comparable.” My point here, generating questions compared to testing is time inefficient.

What did we learn?

So, first, the students preferred revision style from the follow? (a) re-studying the material, (b) active summarizing (e.g., writing notes, summaries, and note cards), (c) elaboration (e.g., visualization, working examples, and consulting further resources), (d) self-testing and explaining to others, (e) generating questions, (f) miscellaneous

Active summarizing strategies (130) followed by re-studying strategies (116). At the other end of the list, self-testing (50), elaboration (19), and generating questions only once.

Results

Students in both experimental conditions scored on average 11% points higher on the final test one week later compared with students in the re-study condition. No significant difference was found between generating questions and testing.

The positive effects of question generation and testing compared with re-studying were also confirmed when factual and transfer knowledge were analysed separately.

We also learn that students in the generating questions condition and in the testing condition took “slightly longer” than students in the re-study condition. The researchers hinting at a deeper commitment?

Takeaway

Generating questions yielded similar effects as testing. “Open-book” approaches such as these, give learners the opportunity to consolidate / correct knowledge (by looking up the information). “Closed-book” testing could accompany this strategy or be employed as a discrete strategy.

As a teacher – know that using your pupils to generate questions is a valid and worthwhile revision strategy. Follow it with a test and testing.

Bae, C. L., Therriault, D. J., & Redifer, J. L. (2019). Investigating the testing effect: Retrieval as a characteristic of effective study strategies.Learning and Instruction,60, 206–214

Donoghue, G. and Hattie, J., (2021). A Meta-Analysis of Ten Learning Techniques. Frontiers in Education, 6.

Ebersbach, Mirjam & Feierabend, Maike & Nazari, Katharina. (2020). Comparing the effects of generating questions, testing, and restudying on students’ long‐term recall in university learning. Applied Cognitive Psychology. 34. 10.1002/acp.3639.

Song, D. (2016). Student-generated questioning and quality questions: A literature review. Research Journal of Educational Studies and Review, 2, 58–70.

Rosenshine, B., Meister, C., & Chapman, S. (1996). Teaching students to generate questions: A review of the intervention studies.Review of Educational Research,66, 181–221. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066002181

Weinstein, Y., McDermott, K. B., & Roediger, H. L. (2010). A comparison ofstudy strategies for passages: Rereading, answering questions, andgenerating questions.Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied,16,308–316

Pingback: Top tips for generating retrieval questions for revision – Edventures